invitation / recto

(FR)

(EN)

(ΕΛ)

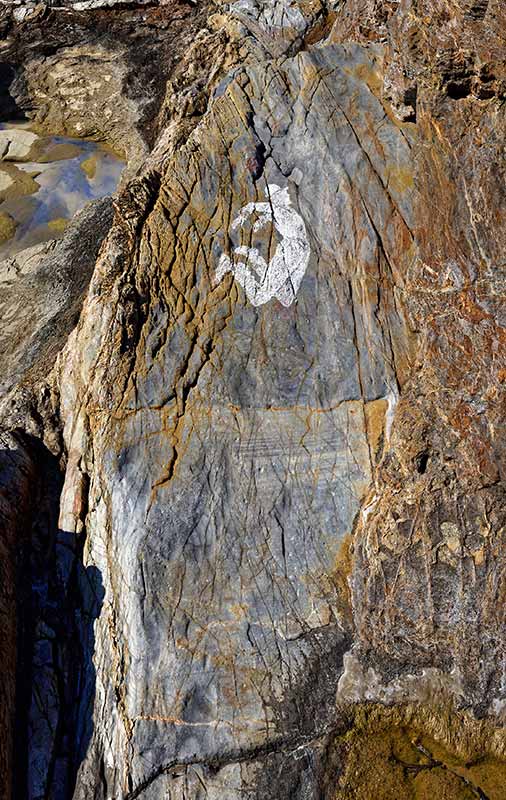

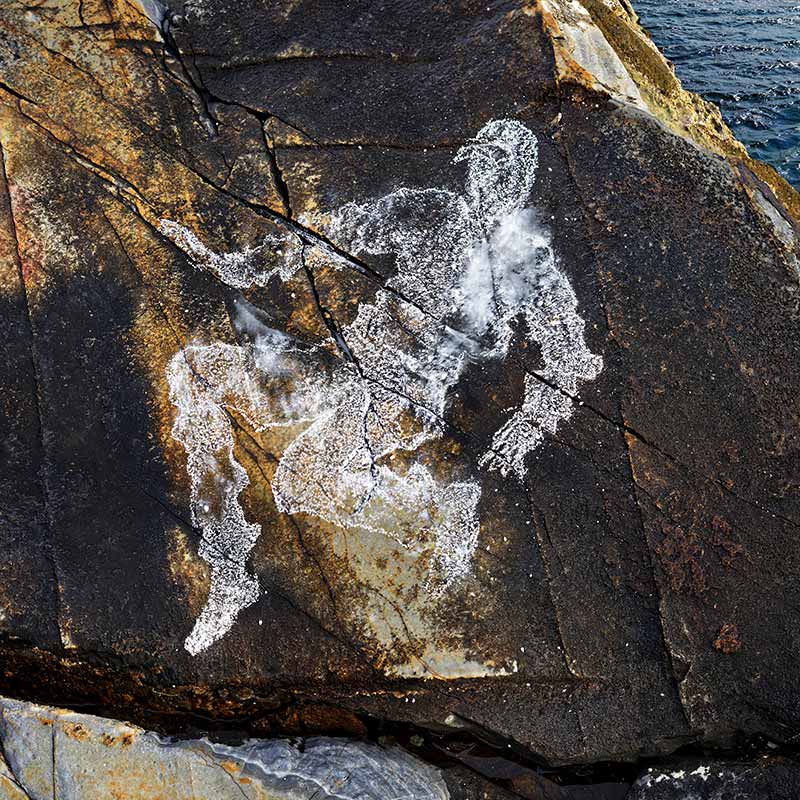

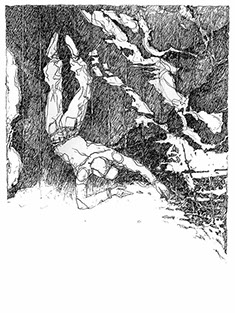

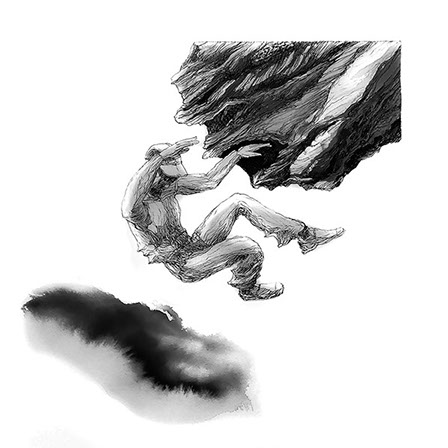

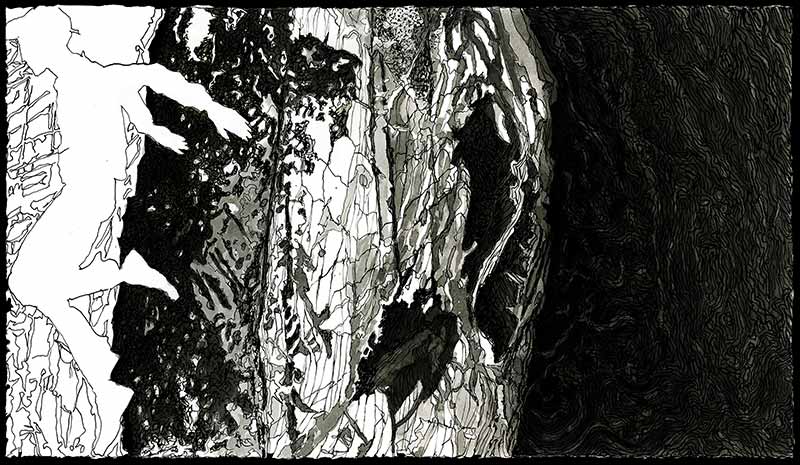

D’un geste de la main une silhouette humaine est apposée à la craie sur la roche. Elle s’élance, vole, chute, dans un état incertain où les lois de l’apesanteur semblent lui jouer des tours. Elle s’inscrit dans un paysage naturel plus vaste, de côtes déchiquetées, de falaises stratifiées, comme abandonnée à l’usure de l’écume et du sel de la mer Egée.

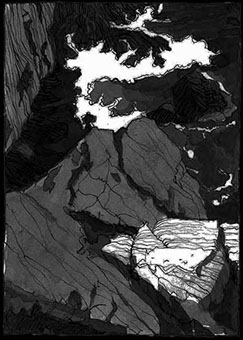

Mais qu’en est-il ? A quelle distance se situe le photographe de son sujet ? Est-il sur le même plan, en aplomb ou en surplomb de l’image saisie ? Cette silhouette humaine est-elle géante ou lilliputienne ? Son tracé est-il défini uniquement par la craie, et n’est-il pas guidé par les strates minérales, les plis de la roche qui prolongent la figure ou la sectionne ?

La perception au premier regard que le travail de Baudouin Colignon s’inscrirait dans la pratique du land-art, dont la photographie constituerait le témoignage naturaliste, nous égare. Quelque chose cloche, trébuche, dans ce que l’on perçoit, une distorsion subtile s’est insérée dans l’image. Ce paysage ne peut exister même si sa représentation semble d’une objectivité incontestable.

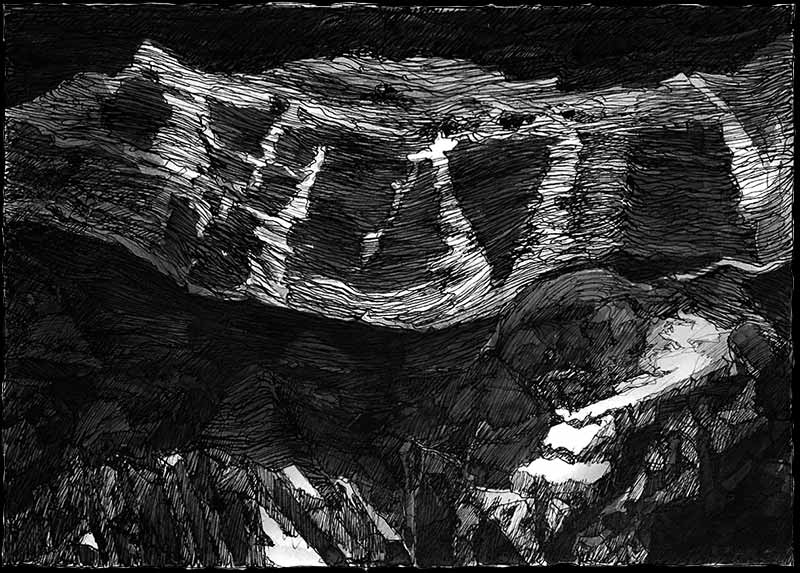

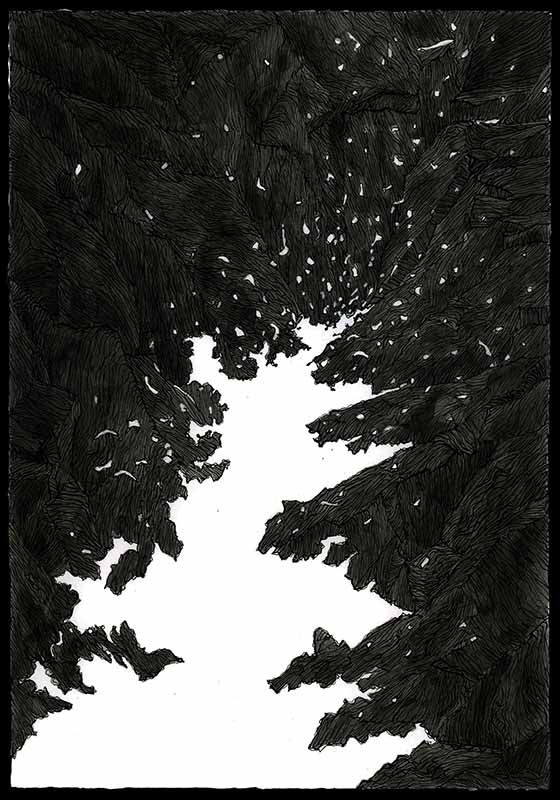

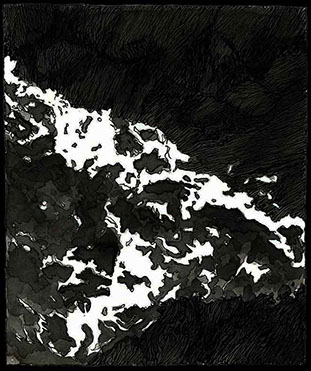

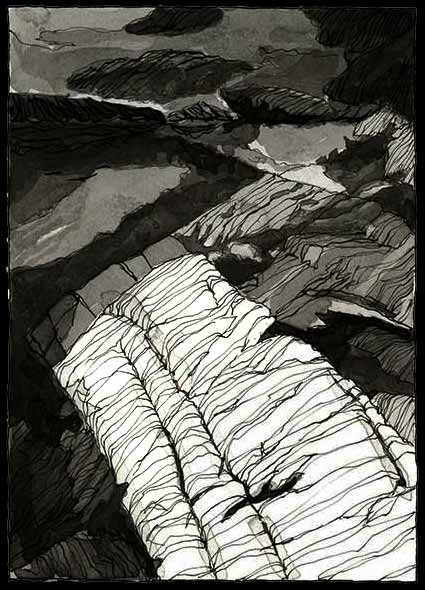

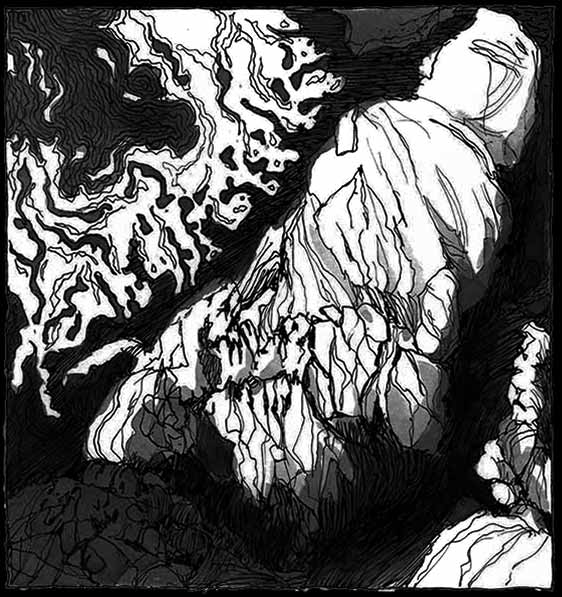

Car si le travail de Baudouin trouve bien son origine dans le land-art, il s’en est éloigné, pour baliser une démarche singulière. Des rivages grecs qu’il arpente systématiquement, à l’atelier où les dessins à l’encre de chine l’aident à apprivoiser la topographie des lieux, c’est par le recours aux technologies numériques de l’image qu’il va pouvoir traquer le point de vue « scientifiquement » juste, puis déployer l’expression d’un paysage mental dans lequel rien de ce que la nature a offert à son regard n’aurait été omis, et où la figure humaine vacillerait.

Philippe Zagouri, salon H

With the movement of a hand a human silhouette is chalked upon the rock. The silhouette leaps, flies, falls, in an uncertain state where the laws of gravity seem to play tricks on him. The silhouette is in a vaster natural landscape of rugged coastlines and layered cliffs, as if abandoned to the wear and tear wrought by the foam and salt of the Aegean Sea.

But what happens? How far is the photographer from his subject? Is he on the same level as the image captured, or below or above? Is this human silhouette gigantic or Lilliputian? Is it defined solely by chalk or is it guided by the mineral strata, the folds of the rock that stretch or sever the figure?

The initial perception that Baudouin Colignon’s workfalls with in the realm of landart, expressed naturalistically through photography, leads us astray. Something’s wrong, misleading in what we perceive, a subtle distortionis inserted in the image. This landscape cannot exist even if its depiction seems to be of unquestionable objectivity.

For while Baudouin’s work does indeed have its roots in landart, it has moved away and maps out its own singular approach. From the Greek shores he methodically surveys to the studio where he uses Indian ink drawings to tame the topography of the places, it is through digital imaging technology that he is able to track the “scientifically” sound point of view, and then to deploy the expression of a mental landscape where nothing that nature has held up to his eyes has been omitted, and where the human figure sways to and fro.

Philippe Zagouri, salon H

Με μια χειρονομία προστίθεται με κιμωλία μια ανθρώπινη σιλουέτα πάνω στο βράχο. Ορμάει, πετάει, πέφτει, σε μια αβέβαιη κατάσταση όπου οι νόμοι της έλλειψης βαρύτητας φαίνεται να της παίζουν παιχνίδια. Εγγράφεται σ’ ένα ευρύτερο φυσικό τοπίο, ακανόνιστα δαντελωτές ακτές, στρωματοποιημένα βράχια, σαν να τα έξυσαν το αλάτι και ο αφρός του Αιγαίου.

Όμως τί συμβαίνει εδώ; Σε ποιαν απόσταση τοποθετείται ο φωτογράφος από το θέμα του; Βρίσκεται στο ίδιο επίπεδο, σε ευθεία γραμμή ή υπεράνω της φωτογραφημένης εικόνας; Αυτή η ανθρώπινη σιλουέτα είναι γιγάντεια ή λιλιπούτεια; Το ιχνογράφημά της ορίζεται μόνο από κιμωλία ή μήπως καθοδηγείται και από τα στρώματα του μεταλλεύματος, τις πτυχές του βράχου που επιμηκύνουν την φιγούρα ή και την τέμνουν;

Η αντίληψη, εκ πρώτης όψεως, ότι το έργο του Baudouin Colignon θα εγγραφόταν στην πρακτική της land-art της οποίας η φωτογραφία θα αποτελούσε τη νατουραλιστική μαρτυρία, μας παραπλανά. Κάτι πάει στραβά, δεν στέκει, σε αυτό που αντιλαμβανόμαστε, μια υποδόρια παραμόρφωση έχει παρεμβεί στην εικόνα. Αυτό το τοπίο δεν μπορεί να υφίσταται, έστω και αν η αναπαράστασή του φαίνεται αναμφισβήτητης αντικειμενικότητας.

Διότι, εάν το έργο του Baudouin έχει τις ρίζες του στην land-art, όμως απομακρύνθηκε από αυτή, για να σηματοδοτήσει μιαν ιδιαίτερη προσέγγιση. Από τις ελληνικές ακτές τις οποίες που μελετά συστηματικά ως το εργαστήριο όπου τα σχέδια με τη σινική μελάνη τον βοηθούν να δαμάζει την χωρογραφία του τοπίου, θα καταλήξει στη χρήση ψηφιακών τεχνολογιών της εικόνας ώστε να είναι σε θέση να εντοπίσει τη σωστή "επιστημονική" άποψη και στη συνέχεια να ξεδιπλώσει την έκφραση ενός πνευματικού τοπίου στο οποίο δεν έχει παραλειφθεί τίποτα από όσα η φύση προσέφερε στο βλέμμα του, και στο οποίο η ανθρώπινη φιγούρα θα βαυκαλιζόταν.

Philippe Zagouri , salon H

décollage 110 x 125

le recoin 104 x 64

vue planante 110 x 125

juste au bord 110 x 125

vue plongeante 104 x 64

(FR)

(EN)

(ΕΛ)

Parmi les énigmes que les commentateurs les plus anciens de l’Odyssée ont tenté de démêler, il en est une qui touche au corps d’Ulysse, divers, diffracté, incohérent, pluriel. Ou pour le dire d’un terme associé au héros lui-même, polytropos, aux manières multiples. Tantôt vieux, tantôt vigoureux, tantôt beau, tantôt hideux, tantôt reconnaissable, tantôt méconnaissable. Au gré des caprices ou volontés d’Athéna, son apparence est mutante, entre métaphore et métamorphose. Sa forme même fait question, bien au-delà des déguisements et jeux volontaires pour tromper l’autre et se sortir des chausse-trappes où les dieux, les hommes et la mer grecque l’auront perdu. Laissons à ces commentateurs le soin philologique de l’érudition. Gardons la trace que cette mémoire aura imprimée en Baudouin Colignon qui, ici, ne représente pas spécifiquement ce personnage.

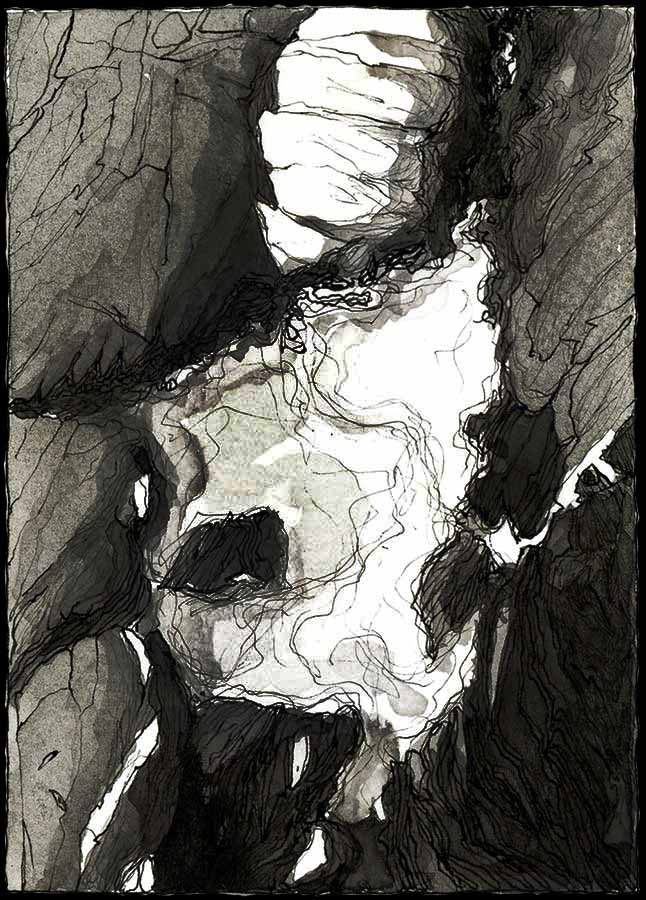

Il dessine un corps d’homme et le confie aux vagues de la mer Égée avec lesquelles, fondamentalement, il inscrit, appose, étale la craie. Il marque à même la roche les bords et les pleins de la forme humaine. Disons qu’il abandonne dans ce travail la géo-métrie, mesure de la terre, de ses anciens travaux pour passer à l’anthropo-morphisme ou forme de l’homme. Disons même, si l’on veut rester dans cette aire de la langue grecque qu’il parle, qu’il trahit le platonisme et fait retour vers Ulysse. Disons surtout que nous sommes, nous spectateurs, des substituts de Pénélope, le voyons-nous ou pas, le reconnaissons-nous ou pas, cet homme-là qui s’absente et revient ? Divers états du travail engagent ici le processus de l’identification d’une forme et d’un être. Diverses techniques compliquent simultanément la figuration. Réemplois, répétitions, anamorphoses, effacements, montage, numérisation, etc. Un instant l’image est lisible, puis elle échappe. A l’encre le corps est plein et entier, à la craie il se brouille et se brise.

Le dispositif complique en outre d’autant plus la lecture que ces corps sont, comme l’indique le titre, en alpha-pesanteur, c’est-à-dire dans un espace incertain de chute et de vide, de réversion et d’involution. Mieux, d’alphabet et de gravité, comme si le tracé de la lettre contestait la loi physique de la chute des corps et lui substituait une expérience de la désorientation : Ulysse encore. Espace de la vague. Espace insulaire. Espace de la fragmentation des terres. Mais surtout espace que Baudouin Colignon balise depuis longtemps en pratiquant non pas la seule géométrie euclidienne du plan mais la topologie, et plus spécifiquement le ruban de Möbius. La place du regardeur est flottante et démultipliée. La forme s’invagine en anamorphose, le volume devient plan et réciproquement, la ligne se perd dans l’infini des mers…

Claire Brunet, enseigne la philosophie à l’Ecole Normale Supérieure de Cachan / Paris Saclay

Among the enigmas in Homer’s Odyssey that scholars have long sought to unravel there is one that concerns the body of Odysseus, diverse, diffracted, incoherent, plural. Or, using a term associated with the hero himself, polytropos, in multiple ways. Now old, now vigorous, sometimes handsome, sometimes hideous, now recognizable, now unrecognizable. According to the whims or wishes of Athena, his appearance is mutant, between metaphor and metamorphosis. His very form poses questions, beyond disguises and games intended to trick the other and escape from traps where gods, men, and the Greek sea lost him. Let's leave philology to the erudition of scholars and keep the trace that this memory has imprinted in Baudouin Colignon who, here, does not specifically depict this character.

Baudouin Colignon draws a man’s body and offers it to the Aegean Sea, with whose waves fundamentally he inscribes, appends, applies the chalk. He marks upon the rock the outline and the solid form of the human body. Let’s say that in this work he abandons the geo-metry, the measure of the earth, of his previous work and shifts to anthropo-morphism, or the form of man. We can even say, if we want to remain within the compass of the Greek language, which he speaks, that he betrays Platonism and returns to Odysseus. Above all, we may say that we, as viewers, are substitutes for Penelope, whether or not we see him, recognize him, this man who leaves and returns. Various stages of the work in progress in volve here the process of identification of a form and of a being. Diverse techniques simultaneously complicate the representation. Re-use, repetition, anamorphosis, erasing, paste-up, digitization, and so forth. One instant the image is clear, and then it's gone. In ink, the body is full and whole; in chalk, it’s blurred and broken.

The scheme is further complicated because these bodies are, as the title alpha-pesanteur indicates, weightless, to wit, in an uncertain space of free fall and void, of reversion and involution. Better still, of alphabet and gravity, as if the tracing of the letter defied the law of gravity and replaced it with an experience of disorientation: Odysseus again. Wave space. Insular space. Space of fragmenting land. But above all a space that Baudouin Colignon has long mapped out not only with Euclidean planar geometry but also topology, and more specifically the Möbius strip. The viewer's placeis floating and magnified. The shape is invaginated in anamorphosis, volume becomes planar and vice versa, the line is lost in the infinity of the seas…

Claire Brunet is alecturer in philosophy at the École Normale Supérieure at Cachan / Paris Saclay

Ανάμεσα στα αινίγματα που έχουν προσπαθήσει να διαλευκάνουν οι παλαιότεροι σχολιαστές της Οδύσσειας, υπάρχει ένα που αγγίζει το ίδιο το σώμα του Οδυσσέα, διαφορετικό, διαφωτισμένο, ασυνάρτητο, πληθυντικό. Ή, για να το χαρακτηρίσουμε για μια λέξη που σχετίζεται με τον ίδιο τον «πολύτροπο» ήρωα, δηλαδή με πολλαπλούς τρόπους. Άλλοτε ηλικιωμένο, άλλοτε δυνατό, άλλοτε όμορφο, άλλοτε φρικτό, άλλοτε αναγνωρίσιμο, άλλοτε αγνώριστο. Έρμαιο των καπρίτσιων ή των επιθυμιών της Αθηνάς, η εμφάνισή του είναι διαμορφωμένη, ανάμεσα στη μεταφορά και τη μεταμόρφωση. Η ίδια του η μορφή είναι ένα ζήτημα, πέρα των μεταμφιέσεων και των εθελούσιων παιγνίων ώστε να εξαπατήσει τον άλλον και να βγει από τις παγίδες όπου θεοί, άνθρωποι και η ελληνική θάλασσα τον έχουν εγκλωβίσει. Ας αφήσουμε όμως στους σχολιαστές τη φιλολογική φροντίδα των ανωτέρω. Κι ας κρατήσουμε το αποτύπωμα που αυτή η μνήμη έχει αφήσει στον Baudouin Colignon, ο οποίος, εδώ, δεν εκπροσωπεί συγκεκριμένα αυτόν τον χαρακτήρα.

Εκείνος ζωγραφίζει ένα ανθρώπινο σώμα και το εμπιστεύεται στα κύματα του Αιγαίου με τα οποία, ουσιαστικά, εγγράφει, προσθέτει, απλώνει την κιμωλία. Σφραγίζει στο βράχο την πλαστικότητα της ανθρώπινης μορφής. Ας πούμε ότι, σε αυτή τη δουλειά, εγκαταλείπει την γεω - μετρία, το μέτρο της γης των παλαιότερων του έργων για να περάσει στον ανθρωπομορφισμό ή μορφή του ανθρώπου. Δηλαδή, αν, συνελόντι ειπείν, μείνουμε σε αυτή την εκδοχή της ελληνικής γλώσσας που υπερασπίζεται ο ίδιος, τότε προδίδει τον Πλατωνισμό και επιστρέφει στον Οδυσσέα. Ας υποθέσουμε λοιπόν ότι είμαστε, εμείς οι θεατές, τα υποκατάστατα της Πηνελόπης, τον βλέπουμε ή όχι, τον αναγνωρίζουμε ή όχι, αυτόν τον άνθρωπο που απουσιάζει και επιστρέφει; Διάφορα στάδια της εργασίας αφορούν εδώ στη διαδικασία προσδιορισμού μιας μορφής και ενός όντος. Ποικίλες τεχνικές περιπλέκουν ταυτόχρονα τη απεικόνιση. Επαναχρήσεις, επαναλήψεις, αναμορφώσεις, διαγραφές, επεξεργασία, ψηφιοποίηση κ.λπ. Για μια στιγμή η εικόνα είναι ευανάγνωστη κι έπειτα ξεφεύγει. Με το μελάνι το σώμα είναι γεμάτο και ολόκληρο, με τη κιμωλία θολώνει και θρυμματίζεται.

Πέραν τούτου, ο μηχανισμός περιπλέκει την ανάγνωση ακόμα περισσότερο, αφού αυτά τα σώματα είναι, όπως το υποδεικνύει ο τίτλος, σε alphapesanteur, αλφαβαρύτητα, δηλαδή σε ένα αβέβαιο χώρο πτώσης και κενότητας, επάνοδος και ανέλιξης. Καλύτερα ακόμα, αλφάβητου και βαρύτητας, σαν το ιχνογράφημα του γράμματος να αμφισβητούσε το φυσικό νόμο της πτώσης των σωμάτων και να το υποκαθιστούσε μια εμπειρία αποπροσανατολισμού: Ξανά ο Οδυσσέας. Χώρος του κυματισμού. Νησιωτικός χώρος. Χώρος κατακερματισμού της γης. Αλλά πάνω απ' όλα, ο χώρος που ο Baudouin Colignon έχει εδώ και πολύ καιρό σηματοδοτεί εφαρμόζοντας όχι μόνο την Ευκλείδεια γεωμετρία του δισδιάστατου επιπέδου αλλά την τοπολογία και ειδικότερα την λωρίδα του Möbius. Η θέση του θεατή κυμαίνεται και πολλαπλασιάζεται. Η φόρμα αναδιπλώνεται σε αναμόρφωση, ο όγκος γίνεται επίπεδο και αντίστροφα, η γραμμή χάνεται στο άπειρο των θαλασσών

Claire Brunet διδάσκει φιλοσοφία στο ENS Cachan / Paris Saclay

Caché dans la lumière, 88 x 65

le grand saut 47 x 72

Paysage de sel 89 x 89

Survol 88 x 65

effacement 96 x 96

culbute 96 x 96

le promeneur, 40 x 40

l'enjambée, 40 x 40

impact, 65 x 50

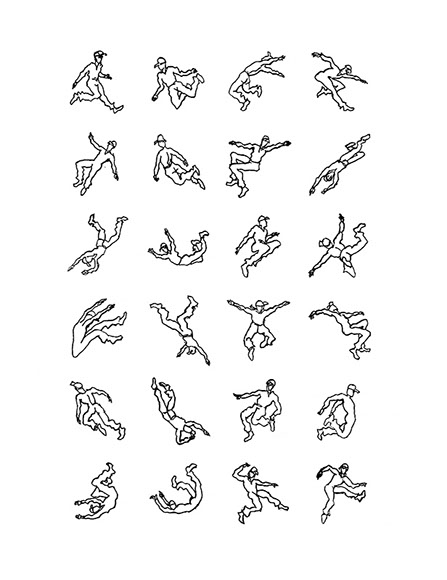

postures, 65 x 50

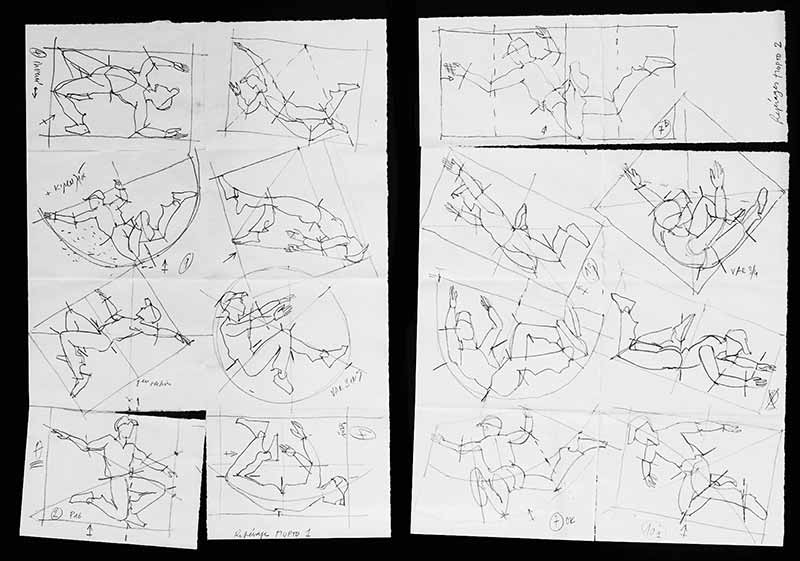

dessins de synthèse avant le tracé in situ, 65 x 50

série "minéralman", 40 x 50

(FR)

(EN)

(ΕΛ)

Pour cette exposition j’ai abandonné un temps mes figures géométriques qui m’accompagnent depuis quelques années, et je me suis attaché à aborder l’anthropomorphisme cher aux Grecs entre le silence de mon atelier et le tumulte du vent des Cyclades.

Dans la nature, tout bouge, l’air, la mer et la lumière, rien n’est stable ni ne s’arrête. À l’atelier, c’est tout le contraire, l’univers est bien réglé, les outils sont en place et le monde technique qui m’entoure me surprend rarement. C’est un espace propice à l’intériorité.

Bizarrement, à l’extérieur, on s’imagine que le «motif" est le lieu chargé d’émotions où l’on doit laisser venir les intuitions, alors qu’en fait c’est un espace difficile à maîtriser que l’on doit contrôler autant que possible pour travailler. Il faut déjà avoir une idée de son sujet avant de s’y installer, et c’est un espace où l’anticipation et la mémorisation sont indispensables.

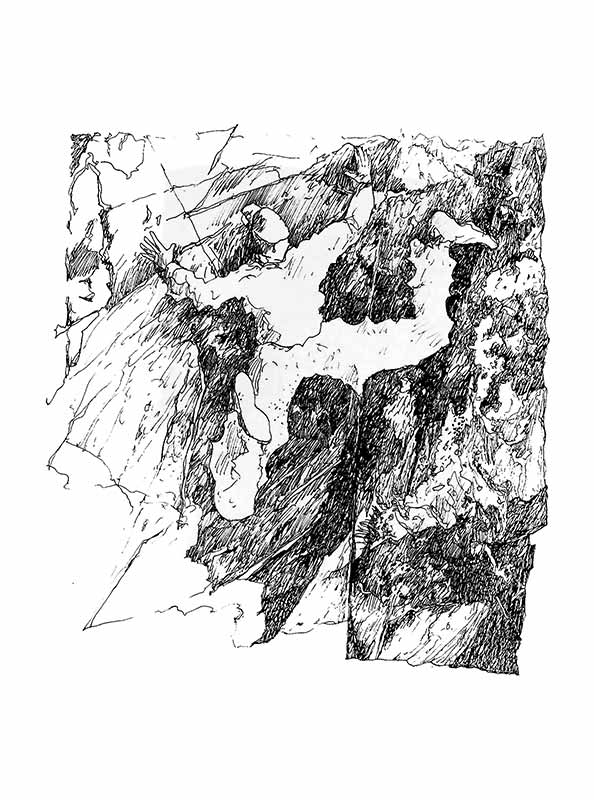

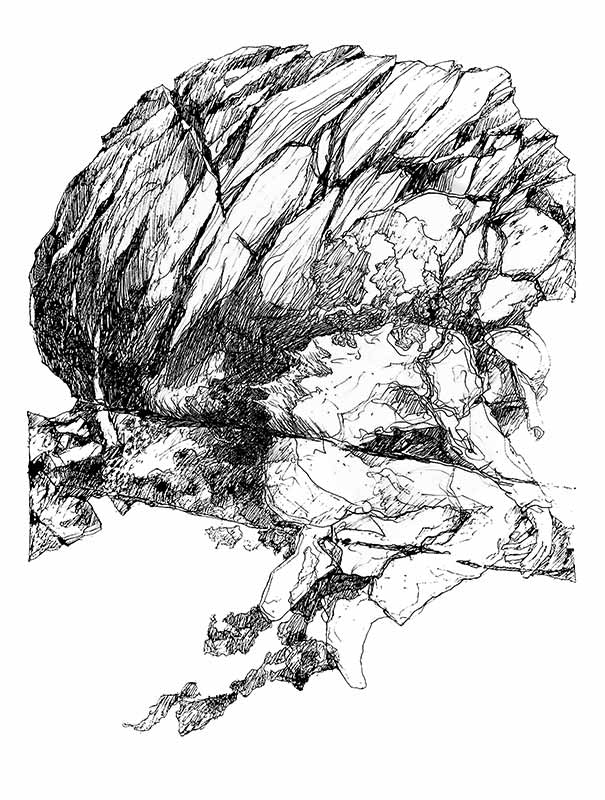

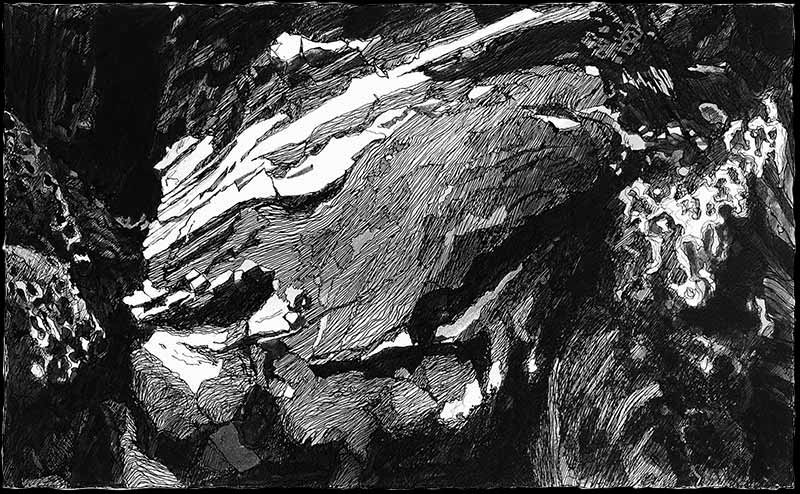

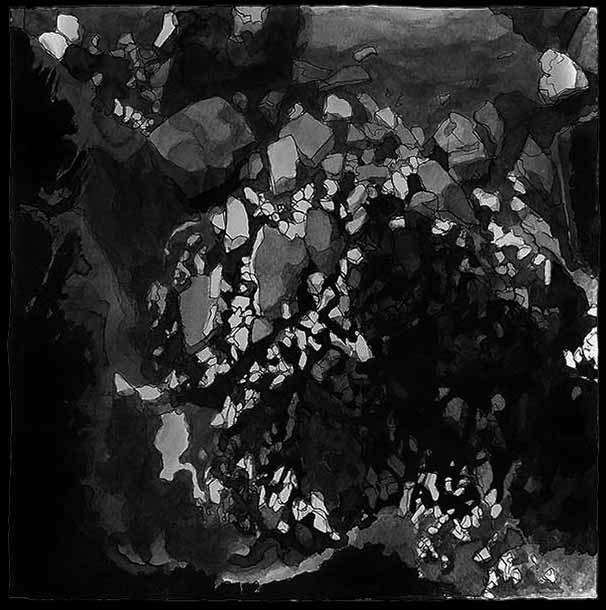

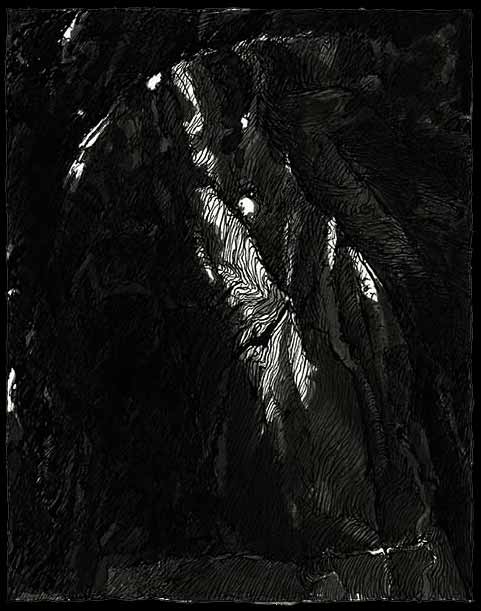

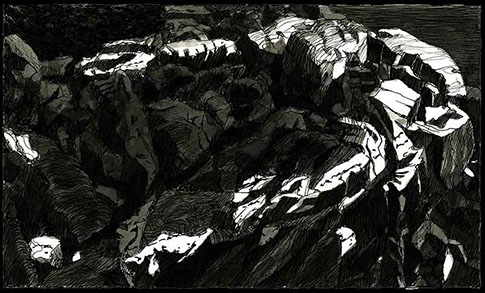

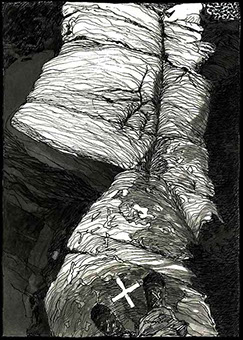

Sur les rochers je dessine toutes mes figures à la craie blanche, et à l’atelier je travaille à l’encre de Chine noire. Le sens de cette opposition trop évidente ne m’est apparu que progressivement au fil des années, et j’ai compris finalement que l’un nourrissait l’autre profondément. Passionné par les diptyques depuis mes premières expositions et face à deux pratiques aussi opposées, j’ai décidé un jour de ne pas choisir et d’organiser mon travail sur cet aller-retour, sans me sentir écartelé. Et pour moi, cette décision m’a libéré de façon durable, car elle m’a permis de donner forme à une recherche qui s’exprime entre plusieurs médias. Le seul point commun à ces pratiques successives reste le dessin.

Que dire de cet aller-retour ? Que d’abord dans cette île, j’ai le plaisir des éléments, mais aussi celui des côtes, des bords. Dans ce genre d’espace limite, on perçoit plus fortement l’activité incessante de la nature. Donc je marche dans les rochers, je longe la mer observant le sol qui ressemble parfois à la terre vue d’avion. Je me perds souvent dans ces échelles différentes, et je cherche à accorder les possibilités du paysage à mon idée initiale, à rendre tout ça réalisable, fluide.

S’ensuit à l’intérieur la mise en place de petits schémas plus techniques qui me serviront plus tard dans le paysage. Des sortes d’aide-mémoire à la projection mentale que je vais devoir faire sur la roche pour que ma silhouette existe. Mais dans la nature, je sais que tout doit s’organiser selon des phases précises pour que ce tracé à la craie blanche puisse se réaliser.

A la fin, entre projection d’eau et séchage, le temps s’accélère pour prendre de très nombreuses photographies. Je ne cherche pas LA photo de l’œuvre. Ce dessin à la craie est unique, et une fois détruit comme il ne restera que les images, j’essaie juste de ne rien perdre. Par rapport au temps de préparation, cette séquence de prise de vues est très courte.

Quant aux dessins à l’encre de Chine, autre partie des pièces exposées, ils jouent un rôle plus mystérieux dans l’élaboration de mes photos. Je les appelle "mes exercices de contemplation". Ils procèdent plus de la compréhension de la roche que de son observation, et ce sont parfois de pures inventions. Mais pendant le temps de leur réalisation qui est très lent, le regard s’affine pour pouvoir enfin choisir dans les séries de photographies celles qui vont constituer l’œuvre finale. Il y a donc une mise à l’épreuve nécessaire des possibilités du regard par celles de la main au cours de ces allers-retours. Et certaines figures pour trouver leur support minéral au bon moment en ont connu plusieurs !

βC

For this exhibition, I abandoned for a while my geometric figures, which have accompanied me in recent years, and tackled the anthropomorphism that was dear to the Greeks, between the silence of my studio and the tumult of the winds of the Cyclades.

In nature everything is in motion, the air, the sea, the light, nothing is stable, nothing is still. In my studio, it’s quite the opposite, a well-ordered space where my tools are in place and the surrounding technical world rarely surprises me. It’s a space that encourages introspection.

Curiously, one imagines that outdoors the “motif” is a place charged with emotions where intuitions come, whereas in fact it’s a space hard to master that must be controlled as best I can if I'm to work. Some idea of the subject matter is needed before setting up, and it’s a space where anticipation and memorising are indispensable.

On the rocks I draw my figures with white chalk, whereas in my studio I work with black Indian ink. The meaning of this obvious contrast only came to me gradually over the years, and I finally understood that the one deeply nurtures the other. Passionate about diptychs since my first exhibitions and faced with these two contrasting practices, I decided one day not to choose between them, but rather to organise my work around this coming and going, without feeling torn. And this decision freed me lastingly because it allowed me to shape a quest that is expressed through several media. The only point in common between these successive practices is drawing.

What of this toing and froing? On this island I have the pleasure of the elements, but also of the coastline, of the shores. In this circumscribed space, I have a stronger perception of the incessant activity of nature. So, I climb over the rocks, walk beside the sea, observe the sun, which sometimes resembles the earth seen from a plane. Oftentimes I lose my way among these different scales and seek to match the possibilities of the landscape to my initial idea, to render everything achievable, flowing.

Once indoors, I produce more technical sketches that will be useful later outdoors, things that jolt my memory and fuel the mental projection that I’ll need among the rocks to bring my figures to life. But outdoors, in nature, I know that everything has to be organised according to precise phases if I am to trace the white chalk outline.

Ultimately, between the splashing of water and drying, time accelerates and I take many photographs. But I’m not seeking THE photo of the artwork. Rather, I try not to lose anything, because the chalk figure is unique and once destroyed all that's left are the images. Compared with the preparation time, this sequence of shots is very short.

As for the Indian ink drawings, the other exhibits, they play a more mysterious role in the working-out of my photos. I call them "my exercises in contemplation." They emerge more from understanding than from observation of the rock, and sometimes they are pure inventions. But as I make the drawings, in what is a very slow process, my ways of seeing are refined so that at the end I’m able to choose from the series of photographs those that will constitute the final work. The possible ways of seeing are then put to the test by the hand's possibilities during the round trips. And in finding their mineral support in a timely fashion, some figures experienced a fair number of comings and goings!

βC

Για την έκθεση αυτή, εγκατέλειψα για ένα διάστημα τις γεωμετρικές φιγούρες που με συνοδεύουν εδώ και κάποια χρόνια, και ασχολήθηκα με τον αγαπημένο των Ελλήνων ανθρωπομορφισμό, ανάμεσα στη σιωπή του εργαστηρίου μου και την αναταραχή του κυκλαδίτικου ανέμου.

Στη φύση όλα κινούνται, ο αέρας, η θάλασσα και το φως, τίποτε δεν είναι σταθερό, ούτε σταματά. Στο εργαστήριo, είναι ακριβώς το αντίθετο, το σύμπαν είναι καλώς συντονισμένο, τα εργαλεία στη θέση τους και ο τεχνικός κόσμος που με περιβάλλει, σπάνια με ξαφνιάζει. Είναι χώρος που ευνοεί την εσωτερικότητα.

Περιέργως, στον εξωτερικό χώρο, φανταζόμαστε πως το «κίνητρο» είναι ένας τόπος φορτισμένος με συναισθήματα στα οποία οφείλουμε να αφήσουμε τις διαισθήσεις να μάς πλησιάζουν, ενώ ουσιαστικά είναι ένας χώρος που δύσκολα δαμάζεται και που πρέπει να ελέγχουμε όσο το δυνατόν περισσότερο για να εργαστούμε.

Πρέπει ήδη να έχουμε μιαν ιδέα για το θέμα μας πριν να εγκατασταθούμε εκεί, και πρόκειται ένας χώρος όπου η πρόληψη και η απομνημόνευση είναι απαραίτητες.

Στα βράχια σχεδιάζω όλες τις φιγούρες μου με λευκή κιμωλία, και στο εργαστήριο τις δουλεύω με μαύρη σινική μελάνη. Η έννοια αυτής της πολύ προφανούς αντίθεσης μού αποκαλύφθηκε μόνο σταδιακά στο πέρας των χρόνων, και συνειδητοποίησα τελικά ότι το ένα τροφοδοτούσε βαθιά το άλλο. Λάτρης των δίπτυχων από τις πρώτες μου εκθέσεις και αντιμέτωπος με δυο πρακτικές τόσο αντίθετες, αποφάσισα μια μέρα να μην διαλέγω και να οργανώνω την δουλειά μου πάνω σε αυτό το πήγαινα-έλα, χωρίς να αισθάνομαι διχασμένος. Αυτή την απόφαση με απελευθέρωνε σταθερά, γιατί μου επέτρεπε να δώσω μορφή σε μια, έρευνα που εκφράζεται με διάφορα μέσα. Το μοναδικό κοινό σημείο αυτών των διαδοχικών πρακτικών παραμένει το σχέδιο.

Τι να πω για αυτό το συνεχές aller-retour; Ότι πρώτα απ’ όλα, απολαμβάνω την ευχαρίστηση των στοιχείων, αλλά και εκείνη των ακτών, των άκρων. Σε αυτό το είδος οριακού χώρου, αντιλαμβάνεται κανείς ισχυρότερα την αδιάκοπη δραστηριότητα της φύσης. Έτσι, περπατώ στα βράχια, κατά μήκος της θάλασσας παρατηρώντας το έδαφος που μοιάζει όπως η γη από αεροπλάνο. Συχνά χάνω τον εαυτό μου σε αυτές τις διαφορετικές κλίμακες και προσπαθώ να συντονίσω τις δυνατότητες του τοπίου με την αρχική μου ιδέα, ώστε να τα κάνω όλα αυτά, ρεαλιστικά, ρευστά.

Ακολουθεί μέσα στo ατελιέ η τοποθέτηση πιο τεχνικών μικρών διαγραμμάτων που θα με εξυπηρετήσουν αργότερα στο τοπίο. Ένα είδος βοηθήματος για την πνευματική προβολή που θα πρέπει να κάνω πάνω στο βράχο έτσι ώστε η σιλουέτα μου να υπάρχει. Αλλά στη φύση, ξέρω ότι όλα πρέπει να οργανωθούν σύμφωνα με συγκεκριμένες φάσεις, έτσι ώστε αυτή η γραμμή με τη λευκή κιμωλία να μπορεί να πραγματοποιηθεί.

Στο τέλος, μεταξύ του πιτσιλίσματος νερού και της ξήρανσης, ο χρόνος επιταχύνεται για να πάρω πολλές φωτογραφίες. Δεν επιδιώκω ΤΗΝ φωτογραφία του έργου. Αυτό το σχέδιο με την κιμωλία είναι μοναδικό, και μόλις καταστραφεί ,καθώς θα παραμείνουν μόνο οι εικόνες, απλά προσπαθώ να μην χάσω τίποτα. Σε σύγκριση με τον χρόνο προετοιμασίας, αυτή η σειρά λήψεων είναι πολύ σύντομη.

Όσο για τα σκίτσα με σινική μελάνη, ένα άλλο μέρος των εκθεμάτων, παίζουν ένα, πιο μυστηριώδη ρόλο στην δημιουργία των φωτογραφιών μου. Τα αποκαλώ "ασκήσεις διαλογισμού μου". Πρόκειται περισσότερο για την κατανόηση του βράχου παρά για την παρατήρησή του, και αυτά είναι μερικές φορές καθαρές εφευρέσεις. Αλλά κατά τη διάρκεια της πραγματοποίησής τους που είναι πολύ αργή, το βλέμμα ακονίζεται προκειμένου να επιλεχθούν στις σειρές φωτογραφιών εκείνες που θα αποτελέσουν το τελικό έργο. Υπάρχει, επομένως, μια απαραίτητη αποδοκιμασία των δυνατότητων του ματιού από αυτές του χεριού κατά τη διάρκεια αυτών αλληλεπιδράσεων. Και μερικές φιγούρες, μέχρι να βρουν την πέτρινη τους βάση, την κατάλληλη στιγμή, έχουν βιώσει πολλές!

βC

grande nuit étoilée, 40 x 40

rochequivole, 50 x 50

point2depart

petra 38

surplomb